In early spring, we often look for signs of new plant growth. In wet, damp sites, such as the edges of lakes, wetlands and seeps, there are a few native herbaceous perennials that start to pop out and that we often get questions about at Hoyt Arboretum. Here are a few interesting facts and identification tips for three peculiar, native herbaceous perennials: skunk cabbage, sweet coltsfoot, and common horsetail.

Skunk cabbage (Lysichiton americanus): While hiking in soggy, damp woods, or even in sites that might still have some snow on the ground, you may come across some bright yellow splashes of color! What is it? Is there a faint skunky-like aroma in the air? You may have come across our native skunk cabbage plant, which is neither a skunk nor a cabbage!

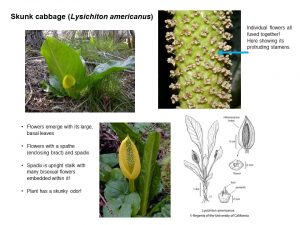

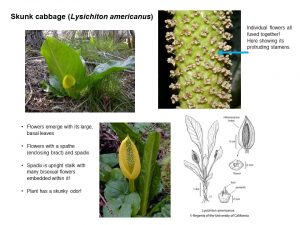

In early spring, skunk cabbage emerges with its flower and leaves. Its floral structure is a specialized type of inflorescence (cluster of flowers) called a “spathe and spadix”, common in members of the Arum family (Araceae). You may have seen these types of flowers in other members of the Arum family, such as jack-in-the-pulpit, the giant corpse flower or titan arum, Anthuriums (an indoor potted plant, often with a bright red spathe) and calla lilies! The spathe is a bract (leaf-like structure) that wraps around and protects its flowers and may function in attracting pollinators with its bright colors. The spadix is an upright flower stalk with many individual flowers all tightly-bound and coalesced together. Individual flowers of skunk cabbage are bisexual (having both stamens and pistils) with parts in fours and is fused at the base with each flower ovary partly embedded into the inflorescence axis. Additionally, some Arum family members (notably the corpse flower) have the ability to heat up the spadix when the flowers are in bloom, in order to promote and spread its odor (similar to rotting flesh in the case of the corpse flower) to attract pollinators. In the case of skunk cabbage, while its flowers have the ability to bloom through snow cover, its spadix apparently does not heat up and provide a warm resting spot for insect pollinators.

So, in wet, boggy sites with poor drainage, look for showy yellow blooms in early spring and eventually huge (up to three feet in length!), basal, almost fleshy, dark green leaves with a distinct aroma. The name Lysichiton is from Greek, indicating a loose tunic, perhaps in reference to its large, deciduous spathe.

At Hoyt Arboretum, look for an individual plant of skunk cabbage in a small seep near the Winter Garden and in the mini-wetland in the middle of the Visitor Center parking lot.

In summary, look or smell for:

- A slight skunky aroma when tromping in wet areas in early spring.

- Bright yellow colors, which indicate its flowers of a spathe and spadix, emerging with its basal leaves from wet muck!

- Take a close up look at the spadix and see if you can determine individual flowers.

- In late spring-summer, look for huge (almost three feet long), basal, almost fleshy simple leaves.

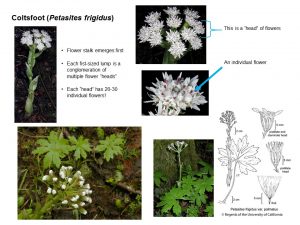

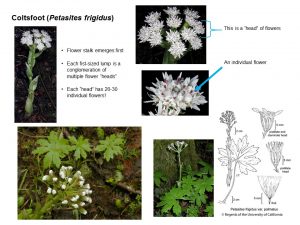

Sweet coltsfoot (Petasites frigidus): The next peculiar plant that we frequently get questions about is sweet coltsfoot. At Hoyt Arboretum, there are patches of it near the Stevens Pavilion and along the Beech Trail below the magnolias. In early spring, its flowering stalk emerges first as a bizarre fist-sized, greenish-white lump, that then develops into an erect, upright fleshy stalk with bunched clumps of white-pink flowers. Its flowering stalks continue rising upwards and then its many flowering “heads” (each a tight cluster of individual flowers) expand outward like an exploding firework! At full bloom its many flower heads, each with a bouquet of individual flowers, is showy and attractive but definitely odd. At flowering, its simple leaves, which are palmately-lobed on long petiole stalks that arise singly from the ground, have appeared and are on their way to becoming large (up to 50 cm wide!) and expansive.

A few details about sweet coltsfoot:

- Perennial, dies back each year.

- Its flowering stalk emerges before its leaves as a greenish-white lump.

- When in bloom, its many separate heads (tight clusters of flowers) expand outwards like a firework!

- Member of the Sunflower or Composite family (Asteraceae).

- Individual flowers are clustered into “heads” (about 20-30 per head), then each flowering stalk may have up to 20 separate “heads”!

- Each flowering head may have two types of different flowers: ray flowers along its outer edges (with straps) and inner disk flowers.

- Leaves can be large (up to 50 cm wide!), palmately-lobed that arise singly on long petioles from the base.

- The name Petasites is from Greek, meaning a broad-brimmed hat, from its large leaves.

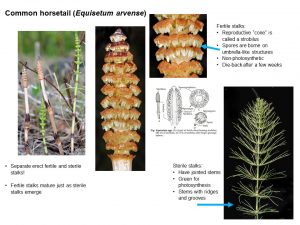

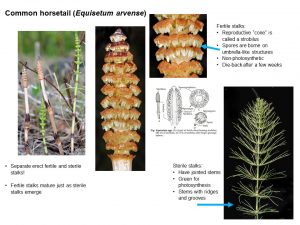

Common horsetail (Equisetum arvense): Our final strange spring herb, as actually NOT a flowering plant. It is considered a “fern ally” (one of those ancient or early-evolved plants) that does not produce flowers, but reproduces using spores as well as vegetatively from underground rhizomes.

Common horsetail is a circumboreal native, meaning that it is widespread and considered a native plant in much of the northern hemisphere and occurs in many places in the Pacific Northwest. Many consider it a “weed” in gardens due to its extensive underground rhizome system. At Hoyt Arboretum, we have a few patches of common horsetail, notably along the Beech Trail and near the connector trails between the Redwood and Creek Trails.

It produces two different growth forms: in early spring it sends up fertile reproductive shoots with a strobilus (a cone-like structure) at its tippy-top that houses its spores, and then it sends up its sterile shoots with the many-jointed stems with which you are probably most familiar. Horsetails are also sometimes called scouring rushes, since they often have high amounts of silica in its stems, so it can be used to scour or scrub dirty pans while camping.

A few other tidbits:

- The name Equisetum is from Latin horse (equus) and bristle (seta).

- Perennial herb that dies back every year.

- Spreads long-range via spores or vegetatively from underground rhizomes.

- Two kinds of erect stems: fertile and sterile.

- Fertile stems emerge first, are fleshy and white-brown in color (no chlorophyll), with reproductive strobilus on top.

- Spores are located on sporangia, that dangle from the edges of peltate scales (like the underside of an umbrella) on the strobilus.

- Sterile stems are green with ridges and grooves, hollow except at nodes.

- Branches are whorled.

- Different Equisetum species can be identified by counting the number of teeth on the stem sheath, and by comparing the lengths of basal internodes to sheath length.

OK, so I hope some of these factoids about our strange and peculiar native plants will enliven some of your walks and explorations this early spring. Stay dry, stay safe, and go outside and look at some plants!

About the Author

Images, diagrams and technical information from:

Mike Drewery

Jepson Manual, Plants of California, eFlora

Oregon Flora website