The Fabaceae is the pea or legume family of plants and are sometimes referred to by their old family name the Leguminosae. Members of the Fabaceae are easily recognizable by their flowers and especially by their distinctive fruits, which are always legumes. Hoyt Arboretum has several notable species of the Fabaceae in our living tree collection, and members of this family are often seen as trail, lawn, and roadside weeds in our region. First, a few interesting facts about the legume family:

- The Fabaceae is the third largest plant family in the world, as counted by its total number of species (behind only the Orchid and Composite/Sunflower family). The Fabaceae has about 750 genera and 19,000 species worldwide! In the 2018 Pacific Northwest Flora, the Fabaceae includes 28 genera and 352 taxa. At the Arboretum, we have 16 genera and 21 species as part of our living collection.

- The old family name – the Leguminosae – refers to its legume fruits. The current family name of Fabaceae comes from (the now obsolete) genus Faba, which today is now included in the genus Vicia. In Latin “faba” means “bean.” Vicia faba is the scientific name for fava/faba beans or broad beans.

- All members of the Fabaceae have fruits that are legumes! A legume is a type of fruit (yes, all flowering plants produce fruits!) that is dry at maturity and is derived from a single carpel. When mature, the fruit opens or splits along two lines of dehiscence. We may eat some edible legume fruits before they fully mature (green beans, sweet peas, sugar snap peas, etc.), and a few members of this family have a specialized type of legume fruit called a loment, which is simply a legume that has its fruit constricted between its seeds.

- Many legumes are edible (when cooked) – in addition to the ones mentioned above, black beans, pinto beans, lima beans, soybeans, etc. are all legumes! Chickpeas or garbanzo beans, split peas, and lentils (the pulses) are also legumes. However, not all members of this family are edible. Lupines (genus Lupinus) can be toxic if ingested, and the genus Astragalus has the common name of locoweed and is highly toxic to livestock (and presumably to humans too).

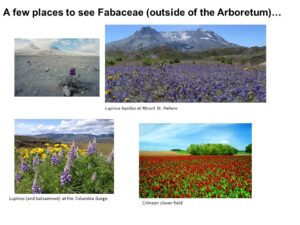

- Legume plants often form symbiotic relationships with nitrogen-fixing soil bacteria. Cover crops such as alfalfa, crimson clover, red clover, etc. are therefore often used as green fertilizer to “add nitrogen” to soils.

- Some members of the Fabaceae have a structure at the base of its leaves at each petiole and petiolule called a pulvinus (seen as a joint-like thickening). This pulvinus works to open and close its leaflets during the day and night (you can see this in the silk tree, Albizia julibrissin at the Arboretum), and in some plants, the pulvinus closes its leaflets in response to touch! If you have ever seen a sensitive plant (Mimosa pudica), it is speculated that its leaflets close to minimize water loss during windy events or to minimize the look of its leaves if an herbivore is browsing.

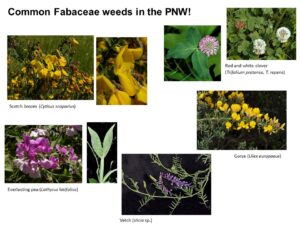

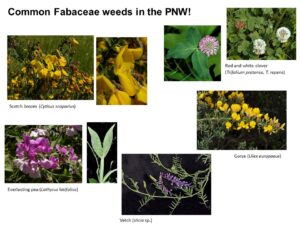

- Some of the most widespread weeds in the Pacific Northwest are in the Fabaceae. Scotch or Scot’s broom (Cytisus scoparius) is widespread in prairies, forest edges and in other disturbed places, such as along the I-5 corridor. Gorse (Ulex europaeus) is invasive in many areas along the Oregon coast, black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) can spread in riparian areas, and vetch (Vicia spp.), peavines (Lathyrus spp.), and red and white clover (Trifolium pratense and T. repens) are common weeds along trails and grassy areas.

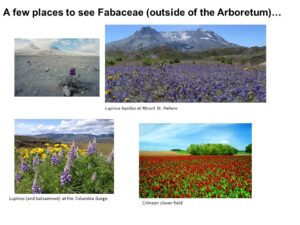

- One of the first seed plants to recolonize the blast zone of Mount St. Helens after its eruption in 1980 was a member of the Fabaceae! It was the dwarf prairie lupine, Lupinus lepidus. This plant has relatively large seeds, so seeds were not dispersed by air; instead, seeds that were buried in soil survived the blast, and when soil was churned and turned by pocket gophers, those seeds germinated and led to its rapid colonization of blast zone areas. The growth of Lupinus ledipus along with its nitrogen-fixing soil bacteria, added much needed nutrients in this blast zone area.

- And yes…peanuts (Arachis hypogaea) are a member of the Fabaceae! Peanut plants do this interesting thing, where its flowers develop near the ground. After its flowers have self-pollinated (!), its developing fruits force themselves into the ground first vertically then horizontally. Its fruits (a legume) then continue developing underground until they mature and are harvested.

Characteristics of the Family Fabaceae:

- Trees, shrubs or herbs

- Plants frequently form a symbiotic relationship with nitrogen-fixing bacteria and form visible nodules on its roots

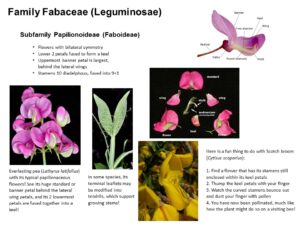

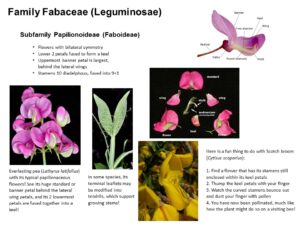

- Leaves are alternately arranged and often compound (pinnately- or palmately-compound, or trifoliate). Note: Cercis is an exception to this with its simple leaves.

- Leaflet margins are usually smooth.

- Flowers bisexual (having both stamens and a pistil) with radial or bilateral symmetry.

- Sepals 5, fused

- Petals 5, all similar or differentiated

- Stamens many or reduced to 10. If 10 stamens, they may be diadelphous (9 fused and 1 free), Pistil of 1 carpel. Ovary is superior.

- Fruit is a legume or loment.

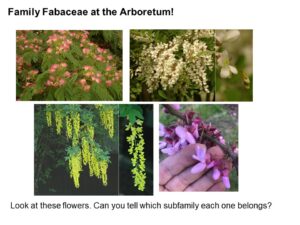

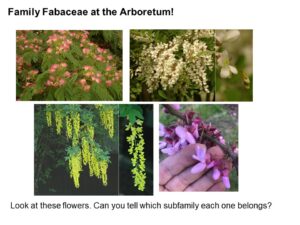

The Fabaceae is also often categorized (by geeky botanists) into three recognizable subfamily groups:

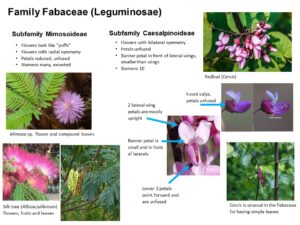

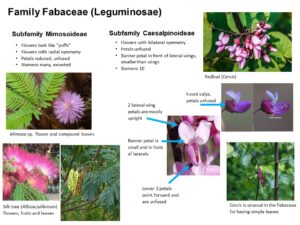

- Subfamily Mimosoideae – Has flowers that looks like poofs! Its flowers have radial symmetry, with small, often inconspicuous and unfused petals. The poofs that you see are its many exserted stamens!

- Subfamily Caesalpinoideae – This group has flowers with bilateral symmetry and its petals are all unfused. If you look closely at its petals, you will see that its uppermost petal (called a standard or banner petal) is situated in front of the lateral wing petals and is often smaller than those laterals. Its two lower petals may protrude forwards but remain unfused. This subfamily typically has 10 stamens, also all unfused.

- Subfamily Papilionoideae (Faboideae) – This subfamily has the largest number of species in the family, and its flowers often resemble butterflies (hence, papilionaceous flowers!). Its flowers are bilaterally symmetrical, its uppermost petal is often the largest and located behind the lateral wing petals. The 2 lowermost petals are fused together to form a keel (like on a boat). It also has 10 stamens, but these are often diadelphous stamens, which means that they are clumped into two separate groupings. In this subfamily, its stamens are 9 fused together, plus 1 more!

At the Arboretum, most of our pea or legume family trees are located where the Overlook, Wildwood and Hawthorn Trails intersect at the top of the hill near a large water tank. In most months, you can observe and examine interesting, showy flowers and/or dangling legume fruits. Can you determine which subfamily the different trees are in?

About the Author

References:

Baldwin, B. et al. (eds.). 2012. The Jepson Manual, Vascular Plants of California, 2nd edition. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Hitchcock, C.L. and A. Cronquist. 2018. Flora of the Pacific Northwest: An Illustrated Manual, 2nd Edition. Edited by D.E. Giblin, B.S. Legler, P.F. Zika, and R.G. Olmstead. University of Washington Press, Seattle, WA.

Zomlefer, W.B. 1994. Guide to Flowering Plant Families. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC.